Note: This story was first published in The Loop Magazine Issue 15 on November 21, 2013.

It’s 2010. A crowd of inner city school teachers have gathered inside the principal’s office. On his desk sits what seems like a giant iPhone to some, a silly device without a physical keyboard to others. To me—someone who had watched Steve Jobs’s iPad unveiling a few weeks before—it looks exactly what Steve called it: a magical thing.

Flash forward to the year 2013, and a number of teachers still remain to be convinced. Who could blame them, when many a “new new thing” has appeared like a godsend yet served only to lengthen teachers’ workloads, adding nothing to sound pedagogy? Look at email. It’s a technology that’s supposed to save us time, and yet, it’s effectively tied us to our desks for longer each day.

Thankfully, the head of learning technologies at my school is an iPad convert. Earlier this year, he ordered 100 iPad minis, still far too few for each student to have one each, but as much as our beleaguered budget would allow in these austerity-ridden times, when UK government cuts are really starting to bite. To encourage take up, we ran a training session where we faced some familiar questions: How can students type long essays on an iPad? I can’t use Microsoft Office in any meaningful capacity—how do you deal with that?

Here’s a rough transcript of what I told the 100-plus staff that crammed into our drama studio on a hot summer’s day in July: “An IOS device is not a replacement for your computer, although your students may beg to differ. If you want to type, use a Mac. If you want Office with all its foibles, grab a PC. Good luck with that. If you want student-centered learning where your youngsters lead on research projects and where the teacher acts as facilitator, choose an iPad. If you want instant Internet to save vital class time, rather than slow-to-load PCs, choose an iPad.”

I went on to use the example of how my history students accessed university research databases and national archives, used the Notes app to bullet point their findings, and dictated a general summary to the rest of the class with a voice-memo app. And not a single student loses anything because the save button is not required in these iCloud times. This last point is important—so many teachers and students still rely on on USB sticks, despite the fact that Dropbox is so much better.

Some other observations I shared with my colleagues:

Avoid subject-specific apps, as they tend to dumb down content. Instead, turn to general apps that can be used in a multitude of learning environments including multimedia functions so that students can have a little fun and be creative with their presentations.

Set up stations of learning just like in Montessori schools with a few iPads at one of those stations to facilitate a research task.

Where possible, have one iPad per student.

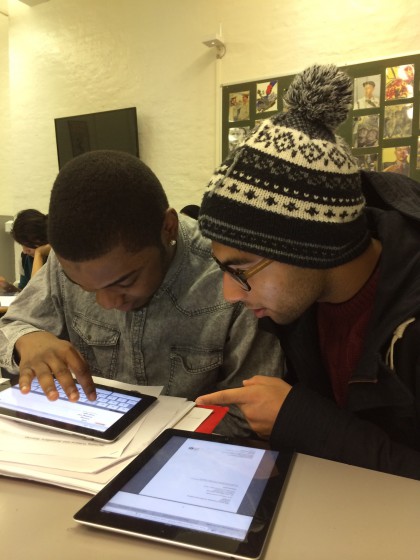

That last suggestion caused some in the audience to balk. “Isn’t education supposed to foster collaboration?” one colleague of mine asked. “How is that achieved when we are all working on separate machines?” Great question. Instead of responding verbally, I had a staff member come and sit by me while I played on my iPad. He just sat there. “How do you feel?” I asked him. “Lonely”, he replied. Then I gave him a spare iPad and we both went onto the BBC News app. Immediately, forgetting the audience, he started speaking to me about a news item, and I shared with him what I was reading on the same app. Now that’s collaboration. Each student should have a separate iPad, but they can still work together to achieve a common end.

I used another example of how a student in a sociology class brought her own iPad to a lesson. She explained to the teacher how she used a sketching app to draw diagrams to help her remember what she was learning and how anything she wrote down on an iPad wasn’t simply copied from the teacher’s PowerPoint to her Pages app. “Using an iPad makes me think about what is being conveyed,” she said. “I feel I understand more when I write on it, as if the information somehow goes through an extra filter that doesn’t exist when I use a pen and paper.”

I promised my audience that I would send them an app a week to try out. They liked that suggestion, but some still had legitimate concerns. At the end of the training, a teacher stayed behind to express her fears about how these devices will be the preserve of the “good kids,” piloted only with those university-bound students who will look after them. At that exact moment, I couldn’t really provide an answer. Until now—until last week in fact, when I planned a lesson for a particularly difficult bunch of students, all with various needs and with outside barriers to learning. I opted for a snazzy start, presuming the iPads’ “new new thing” would provide one. What followed was not the bells-and-whistles lesson that I had hoped for, but chaos didn’t ensue, either. Instead, the result was a surprisingly calm, purposeful lesson where the hitherto problem students engaged fully in what they were doing. Which leads to my next observation: iPads are brilliant for behavior management and should be targeted at all students, particularly the naughtiest.

We are just getting started with these magical devices. It’s going to be an interesting year.

Nick de Souza’s Bio:

Nick lives and works in London, UK, and teaches History and Politics at a school for 16-19 year olds. He used to write for World Link, the magazine of the World Economic Forum, and served in the European Commission’s press department. Teaching remains his passion, yet it faces a run for its money from his love of iPads.